Temple House by J. Kidman, Golden and Studio Tali Roth

Home to a family and their significant art collection, Temple House by J. Kidman – with interior design by Golden and decoration by Studio Tali Roth – represents a considered meeting of several creative minds.

This project existed long before the site was secured – in the form of an ongoing discourse between architect James Reid and his clients, who all met while studying graphic design years ago. The opportunity to work together finally materialised when the clients purchased a larger parcel of land in Melbourne’s inner suburbs. The art-collecting clients – who Reid describes as “real bowerbirds” – applied a similar mentality of assemblage to the project, bringing together a stellar team including Golden and Studio Tali Roth. “As patrons of the arts, the clients liked the idea of engaging people to design something custom and suited to them, as opposed to simply buying a house,” says Reid.

Reid assessed the site’s conditions, context and orientation, as well as its position on the suburban block. Given the north-facing street frontage, he pushed the dwelling towards the rear. “It’s weighted towards the back, so it gets a north-facing front yard and open space as opposed to a house shading its own backyard,” he explains. In addition, the program has been flipped, with the communal living areas at the front and the private spaces towards the back. These respective zones are contained within separate pavilions tacked onto a linear form stretching the length of the western boundary, and the front door is located halfway along, meaning visitors arrive in the heart of the home.

The home’s entry vestibule is an important moment of transition and reflection. Sandy-hued travertine floors are an extension of the external materiality, and natural light bounces deeper into the plan. A Jonny Niesche piece is suspended from the ceiling, and a large painting by Juan Ford spans the opposite wall, setting a strong precedence for the extraordinary art curation that follows.

Golden’s defining challenge involved bringing together the clients’ contrasting tastes. “The primary brief was to create a family home that thoughtfully balanced the clients’ differing design preferences, merging the elegance of refined Belgian minimalism with a more crafted and layered aesthetic,” says Golden’s Alicia McKimm, adding that “each client came to the project with their own custom-made books of reference imagery, and it was our role to interpret and harmonise those distinct visions into a cohesive and liveable whole.”

Similarly, Tali Roth introduced additional gravitas to the project, sourcing furniture, lighting and objects from around the globe. “Sometimes in a large project like this, the furniture can be neglected from decision fatigue or just generally running out of steam,” says Roth. “I wanted to make sure the furniture and lighting made the home even better.” An olive Camaleonda sofa by Mario Bellini is a stand-out piece alongside a brushed stainless-steel dining table designed by Roth and chairs from Ellison Studios.

Unlocking Temple House’s unusual floor plan ultimately produced many of its defining influences. “In the early stages of planning, we realised the project’s layout shared DNA with that of spaces like cathedrals and basilicas,” says Reid. This led him to investigate Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House, Jørn Utzon’s Can Lis and the Scarpa Wing at the Museum Gypsotheca Antonio Canova, which he describes as having “a domesticated monumentality or an intimate, small-scale grandeur”, along with Dani Karavan’s White Square in Tel Aviv.

Greater than vague touchpoints or loose stylistic references, Reid’s thoughtful interpretation of these architectural north stars can be seen throughout the project. Take the dwelling’s exaggerated upper volume, which chamfers inwards; it’s a clear nod to Hollyhock’s monolithic top and an elegant response to the site’s conditions. Also notable is the complex yet highly resolved interplay of stacked volumes and precisely placed openings akin to the pure geometry of Can Lis in Mallorca. Similarly derived from Reid’s interest in Gestalt principles, it creates a pleasing, legible arrangement where the slightest separation creates just the right amount of tension.

These references are at their most striking in the double-height ‘great room’, which contains the open kitchen, living and dining areas. Soaring ceilings, generous zoning and considered sightlines create a space that is at once cocoon-like and monumental. At ground level, the northern elevation features wall-to-wall glass, save for a central column, while the upper portion of the walls are lined in timber, giving the effect of a weighty volume hovering atop a diaphanous form. Thin panes of glass at either end frame slithers of blue and throw natural light across the travertine floors and timber-clad walls.

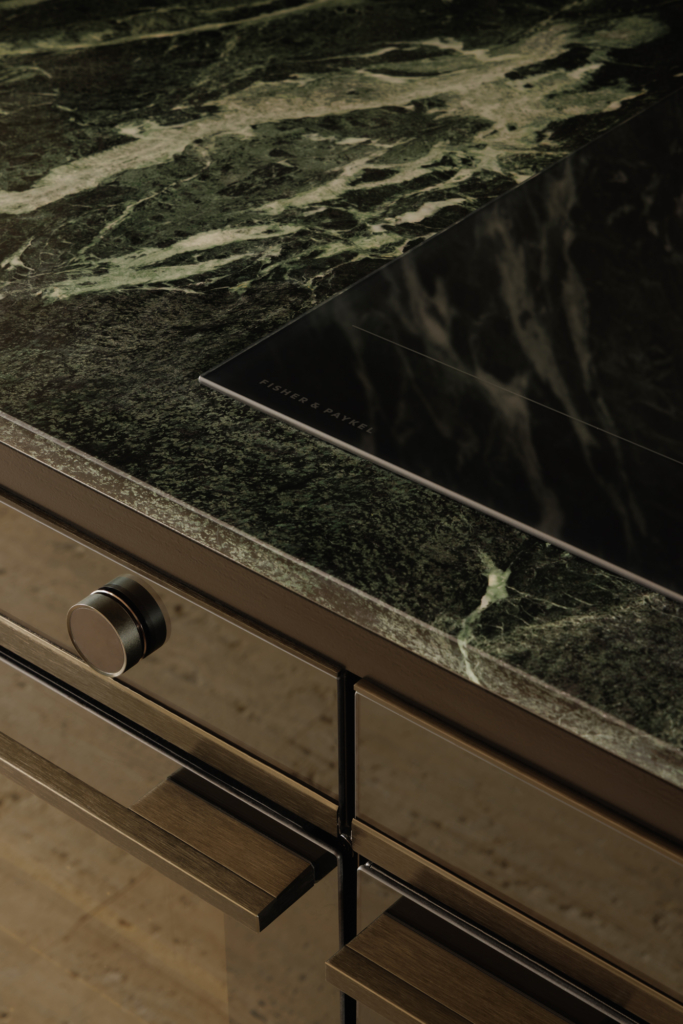

The unique layout places the kitchen in the centre, bookended by the dining space on one end and the living on the other. McKimm “approached the design as though it were a piece of furniture: sculptural, intentional and beautifully resolved without compromising on everyday functionality”. The result is a pair of statement islands draped in emerald marble; together, they anchor the program, acting as both a springboard and a place to pause.

The success of this space lies in the carefully considered composition guided by the height of these twin islands. Full-height refrigeration would have disturbed the balance – Fisher & Paykel’s below-bench CoolDrawers were the answer. “From the earliest sketches on paper, we knew we needed some sort of refrigeration that fit into those island benches, so the design was almost made possible by being able to integrate refrigeration at a low, under-bench level,” says Reid. This is supported by a generous scullery housing larger appliances, including Fisher & Paykel’s Column refrigerator and freezer, which allowed “the main kitchen to remain sculptural and refined, free from the visual bulk of full-height joinery,” says McKimm. It also means that the clients have easy access to high-use, everyday items in the under-bench cooling, with greater storage capacity in the scullery.

The result caters well to the clients, who are “great, natural hosts,” says Reid. Fisher & Paykel ovens, dishwashers and an induction cooktop – as well as a DCS Grill in the outdoor kitchen – round out the selection. Their minimal designs and low-key colour palettes recede into the background, ensuring the kitchen’s materials and sculptural tropes receive full attention.

This pursuit of quiet and clarity applies to Temple House’s overall rationale, which was intentionally conceived to complement family life. “The clients have three kids, so that’s a degree of busyness. Pair that with their everyday routines and eclectic collection of art, and we knew there would be noise and colour, so the house is a minimal backdrop.”

Despite this, Reid was wary of paring the design back too much, preferring a sort of amplified simplicity. “The far end of the spectrum can be too minimal, sort of lifeless, but somewhere before extreme, dogmatic minimalism, there’s a point that’s visually quiet but still charged with an energy,” he says. Consequently, bouts of liveliness abound – from the tension between volumes and unexpected apertures to the dynamic effect of the great room’s dual ingress and egress points – culminating in Reid’s interpretation of élan vital, which loosely translates to vital force. “It’s hard to see on a plan, but those little moves mean the architecture can be minimal – but there’s a charge there, and that makes it feel alive.”

Architecture by J. Kidman. Interior design by Golden. Interior decoration by Studio Tali Roth. Build by Overend Constructions and Form Landscaping. Landscape design by Plume. Engineering by WebbConsult. Joinery by Overend Constructions. Artwork by Rachelle Austen, Michael Georgetti, Jonny Niesche, Nabilah Nordin and Darren Sylvester.